Rita J. King went to Ischia in 2013 to learn more about her family’s roots in the island’s volcanic soil. When she told the hotel clerk that her great-grandfather's last name was Ferrandino, he revealed that Ischia was full of Ferrandinos because Fernando Francesco d'Ávalos was a prolific lover in the 1500s. Ironically, he did not have children with his wife, Vittoria Colonna, patron, poet, and Michelangelo’s intellectual soul mate.

In Florence, Rita waited in line to see Michelangelo’s David but was more attracted to the unfinished blocks near it, the so-called “slaves” originally intended for Pope Julius's II tomb. She learned how Michelangelo was maniacal about picking out his blocks of marble in Carrara, and how the genius of the David was that he carved it from a rejected block of poor quality marble. Rita began thinking about the hidden stories inside uncarved blocks and how they were more intriguing than the perfect, polished final product.

Rita returned home with the best travel souvenir possible — a new fascination. She felt a deep connection to Vittoria Colonna and began studying her letters to Michelangelo. Her newfound ancient friends took root in her imagination. From pondering how Vittoria was able to carve out a public creative life as a woman in the 1500s, an idea for a novel began to emerge.

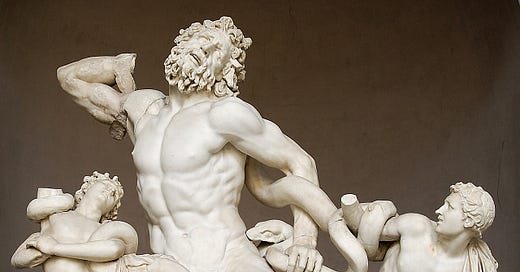

Research on Michelangelo led Rita to fall in love with the exquisite lines and muscles he carved into Carrara marble. But her newly trained eyes got snagged on the Laocoön, carved in 200 B.C.E. because the lines and muscles of the priest who had tried to expose the ruse of the Trojan Horse looked just like Michelangelo’s.

She went back to the books and read how the Laocoon was known in the Renaissance from a translation of Pliny, first written in the first century C.E., describing the Laocoön, a Greek sculpture in the villa of Tiberius, as the single greatest work of art in history. Its marvel rested on the complex composition of the priest, his sons, and snakes having been carved from a single block of marble.

On January 14, 1506, the Laocoön was found in a cistern beneath a vineyard owned by a man named Felice de Fredis. Pope Julius II sent architect Giuliano da Sangallo to investigate and he brought along his buddy, fellow Florentine Michelangelo. Sangallo identified the mostly intact sculpture as Pliny’s Laocoön even though it was composed of seven pieces of marble instead of one. The Pope purchased it from De Fredis on March 23rd for his newly finished Belvedere Court for Greek and Roman sculpture. It’s still there today as part of the Vatican Museums. Rita thought…it was all just a little too perfect.

Rita dug deeper, thinking about how Michelangelo had learned to sculpt from copying classical sculptures in the Medici gardens. He became so good at imitating Greek and Roman sculptures that he carved a sleeping cupid, buried it in the garden, and then passed it off to a wealthy cardinal as an ancient original. She thought about Michelangelo’s need to reinstate his family’s lost fortune and about the great wealth he amassed while his biographers, who he hired and paid, claimed he was always a breath away from bankruptcy. Then Rita wondered if anyone else had accused Michelangelo of being an art forger.

Dr. Lynn Catterson, an art historian with a Ph.D. from Columbia University, had arrived at the same conclusion in 2000. Her paper published in 2005 goes into great detail by interrogating mysterious bank deposits and Michelangelo’s whereabouts in 1506, and other related artworks. The official case she makes in a peer-reviewed journal has completely convinced me that Michelangelo carved the Laocoön.

Her original proposal presented at a conference in 2004 made as much of a splash as academic research can make, garnering coverage in the New York Times. Predictably a small chorus of very established scholars aggressively dismissed the idea, some without even having read her paper. Though no research ever refuted her claim, the deafening silence from the rest of academia ended the conversation.

Twenty years later Francesco Colafemmina, an Italian classicist and beekeeper excavated Dr. Catterson’s work and wrote a book with even more evidence to prove the case. She wrote the book’s forward and said, “it was, and always has been, a thought experiment—meaning that I did not care if I was right or if I was wrong.” She is happy to leave the work in Colafemmina’s capable hands.

Is it even worth looking back at history to try and correct the record? That the Laocoön is the story of an ancient whistleblower seems to carry its warning. But Rita believes that the greatest testament to Michelangelo’s genius is that 500 years later she’s still digging into his work and looking for hidden meaning. Why? Because that’s the beauty and purpose of art in our lives.

For another art history mystery, listen to me discuss the Unicorn Tapestries and the security guard who loved them on the latest episode of the Cultural Debris podcast.

Apple: https://apple.co/3j7Mppi

Spotify: https://spoti.fi/3NOx5fv

Tante Belle Cose is a free newsletter. To support my work, learn with me online via Context Travel where I offer weekly seminars about Italian art, culture, and history.

See my upcoming seminars: https://www.contextlearning.com/collections/danielle-oteri

Such an interesting article, thank you.